Cuisine Nutrition Calculator

For this combination:

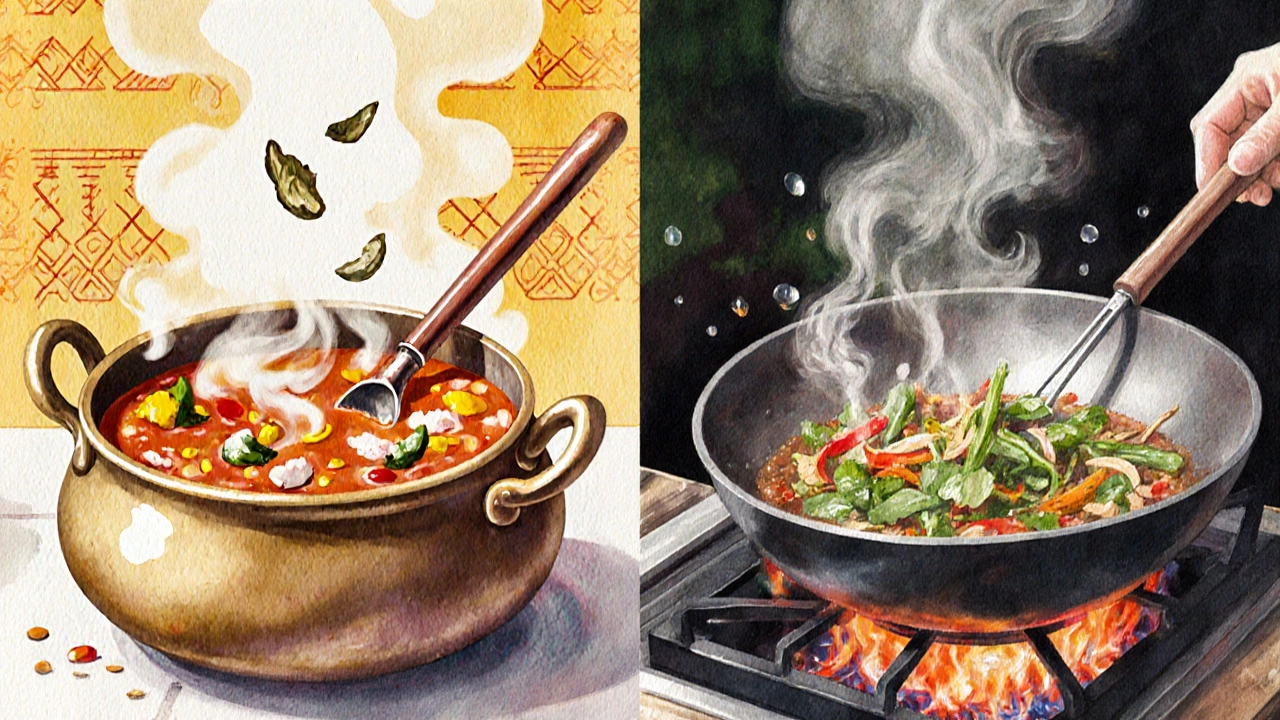

Ever stared at a menu and wondered whether an Indian curry or a Chinese stir‑fry is the smarter choice for your waistline? You’re not alone. Both cuisines are beloved worldwide, but they differ in spices, cooking oils, and typical portions. This guide breaks down the nutrition facts, cooking habits, and ingredient choices so you can decide which plate lines up with your health goals.

What’s the difference in a nutshell?

Indian cuisine is a diverse culinary tradition from the Indian subcontinent, built around spice‑rich sauces, legumes, and a mix of vegetarian and meat dishes. It leans heavily on ghee (clarified butter prized for its high smoke point and buttery flavor) and a wide array of vegetables, lentils, and whole‑grain breads.

Chinese cuisine is a regional food culture from China, best known for quick stir‑fries, soy‑based sauces, and rice or noodle staples. The cooking style often calls for soy sauce (a salty fermented condiment that adds umami depth) and oils like peanut oil (oil with a high smoke point and a nutty flavor).

Macro‑nutrient snapshot

To compare the two, let’s look at typical home‑cooked dishes: a chicken tikka masala with basmati rice versus a chicken chow mein with wok‑fried vegetables. Below is a quick cheat‑sheet of average values per serving (≈250g).

| Metric | Indian plate | Chinese plate |

|---|---|---|

| Calories | 480kcal | 420kcal |

| Protein | 28g | 30g |

| Total fat | 22g | 15g |

| Saturated fat | 9g | 3g |

| Sodium | 850mg | 1,200mg |

| Fiber | 6g | 4g |

| Glycemic index (GI) of carb base | 58 (basmati) | 75 (white rice noodles) |

From the table you can see that a typical Indian plate packs a bit more calories and saturated fat, mainly because of ghee. The Chinese version, on the other hand, tends to be lower in fat but higher in sodium thanks to generous pours of soy sauce. Both sides deliver solid protein, but the Indian side often gives you more dietary fiber if you include lentils or chickpeas.

Key ingredients and their health impact

Let’s unpack the star players in each cuisine.

- Turmeric (a bright yellow spice containing curcumin, known for anti‑inflammatory properties) - a staple in many Indian curries. Studies from 2023 show curcumin can modestly lower C‑reactive protein, a marker of inflammation.

- Ginger (root used fresh or powdered, helps with digestion and may reduce nausea) - common in both Indian and Chinese soups.

- Tofu (soy‑based protein that’s low in saturated fat and a good source of calcium) - featured in many Chinese stir‑fries and some Indian “paneer” alternatives.

- Peanut oil (oil with a high smoke point, but relatively high in omega‑6 fatty acids) - can tip the omega‑6/omega‑3 ratio unless balanced with omega‑3 sources.

- Brown rice (whole grain with more fiber and lower GI than white rice) - increasingly used in both cuisines for a healthier carb base.

Overall, the Indian pantry leans on spices with proven antioxidant benefits, while the Chinese pantry includes more soy‑derived protein and fast‑cooking oils. Both have healthful components; the trick is to use them wisely.

Cooking methods that matter

Technique can swing a dish from “just tasty” to “nutrient‑smart.”

- Slow simmer vs. high‑heat stir‑fry - Indian curries often simmer for 20-40minutes, allowing spices to release their antioxidants. Chinese stir‑fries cook in a flash, preserving vegetable crunch and vitamin C but sometimes requiring extra oil to prevent sticking.

- Steaming - a common Chinese method (think dim sum) that adds almost no fat. Indian “steamed idli” or “dhokla” offer the same low‑fat advantage.

- Grilling/roasting - both cuisines use tandoor (Indian) or char‑broiled meats (Chinese). Grilling adds flavor without extra oil, but watch for charring which can create harmful compounds.

When you aim for a healthier Indian food plate, favor simmered or steamed dishes, trim excess ghee, and load up the lentils. For a Chinese-inspired meal, go for quick stir‑fry with a splash of low‑sodium soy sauce, plenty of veg, and a modest drizzle of oil.

Portion control and calorie density

Even the healthiest ingredients can tip the scale if you overeat. Here are some practical cues:

- Rice portion - ½ cup cooked (≈100g) is a good baseline. Indian biryani often uses more; Chinese fried rice can be calorie‑dense if coated in oil.

- Protein serving - aim for a palm‑sized portion (≈120g) of chicken, fish, or tofu.

- Veggie bucket - fill half your plate with non‑starchy veggies. Indian dal, bhindi (okra), or Chinese bok choy all fit the bill.

- Sauce moderation - a tablespoon of creamy curry or a teaspoon of soy sauce adds 20-30mg sodium and a burst of flavor without drowning the dish.

Practical tips for a healthier blend

Can you enjoy the best of both worlds? Absolutely. Try these swaps:

- Replace heavy cream in butter chicken with low‑fat Greek yogurt (rich in protein, low in saturated fat).

- Swap regular soy sauce for a low‑sodium soy sauce (contains up to 40% less salt).

- Use olive oil (high in monounsaturated fats, good for heart health) for Indian tempering instead of ghee for a lighter fat profile.

- Incorporate more legumes - chickpeas, lentils, or mung beans - to boost fiber and plant protein.

- Choose whole‑grain noodles (e.g., soba) or brown rice over refined white rice to lower the glycemic impact.

These tweaks keep the flavor fireworks while trimming unnecessary calories, saturated fat, or sodium.

Quick takeaways

- Indian dishes often deliver more fiber and antioxidant‑rich spices but can be higher in saturated fat and calories if cooked with lots of ghee.

- Chinese meals usually contain less fat but more sodium, especially when soy sauce is used liberally.

- Cooking method matters: simmered curries and steamed dim sum are nutrient‑friendly; deep‑fry and heavy‑cream sauces add extra calories.

- Control portions of rice, sauce, and oil to keep the meal balanced.

- Smart swaps-low‑fat yogurt, low‑sodium soy, olive oil, whole grains-let you enjoy both cuisines without compromising health.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Indian food always higher in calories than Chinese food?

Not necessarily. It depends on the cooking method and ingredients. A vegetable‑heavy Indian dal with brown rice can be lower in calories than a cheese‑laden Chinese fried rice. Look at the recipe, not just the cuisine.

How can I reduce sodium in Chinese stir‑fry?

Swap regular soy sauce for low‑sodium versions, use fresh garlic, ginger, and a splash of citrus instead of extra sauce, and limit the amount of any packaged sauces.

Are there vegan options in both cuisines?

Absolutely. Indian cuisine offers chana masala, aloo gobi, and lentil soups. Chinese cuisine has tofu stir‑fry, vegetable lo mein, and mushroom hot pot. Both are rich in plant‑based proteins.

Which cuisine is better for heart health?

If you choose dishes that limit saturated fat (use olive oil instead of ghee) and keep sodium low (use low‑sodium soy), both can be heart‑friendly. The key is ingredient choice and cooking technique.

How do I control portion size when eating out?

Request half the rice, ask for sauces on the side, and fill half your plate with vegetables. Many restaurants will accommodate these simple requests.